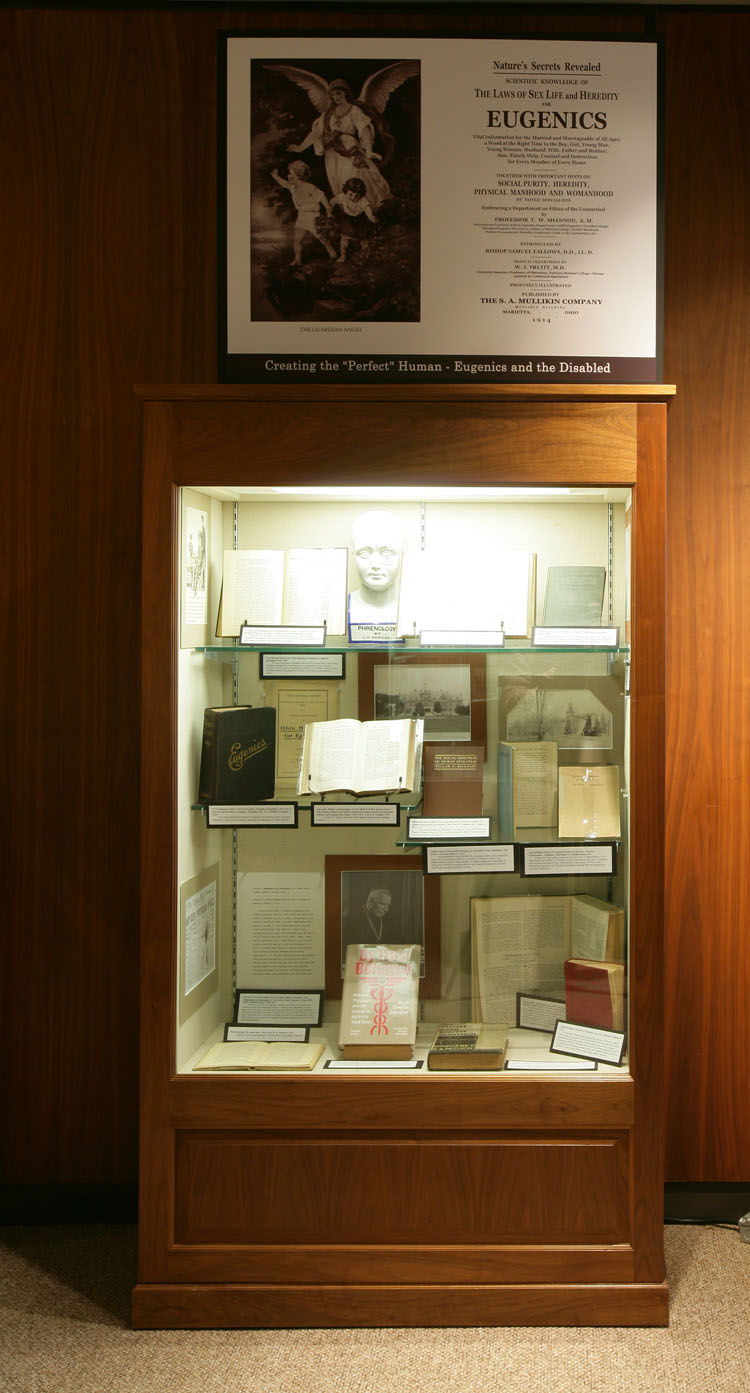

Creating the “Perfect” Human—Eugenics and the Disabled.

Eugenics is the “science” of improving the human race through means such as selective breeding and sterilization. Supporters believed eugenics would increase the intelligence of humanity, conserve resources, and alleviate suffering. The term was first coined in 1883 by Sir Francis Galton, a cousin of Charles Darwin. Inspired by Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, Galton studied whether human ability was an inheritable trait. He suggested improving the species by encouraging able-bodied couples to have more children, and prohibiting “defectives” from reproducing.

Eugenics advocates applied numerous techniques to determine who was fit to reproduce. One of the oldest was physiognomy and its close cousin, phrenology, both of which involved the study of physical traits to determine character and intelligence. This led scientists to associate certain facial and skull features with feeblemindedness, criminality, and other negative traits. Racist beliefs were also based on these “scientific” traits.

Social Darwinism was based on the writings of Herbert Spencer and Thomas Malthus. Spencer, a philosopher and political and sociological theorist, coined the phrase “survival of the fittest.” He believed that human existence is full of struggles that result in winners and losers, and to interfere with this process was counterproductive. Thomas Malthus, a political economist and demographer, believed a certain portion of humanity was relegated to poverty due to the population expanding faster than available resources. Famine, disease, and war acted as natural population reducers, and weeded out many “unfit,” particularly the disabled.

The intellectual discussion regarding the “unfit” turned into action in the 20th century. A popular film of the day encouraged parents to let disabled babies die. In Ohio, eugenics was espoused by John Williams Jones, superintendent of the Ohio State School for the Deaf, who discussed the need to control the population of the disabled in The Greatest Problem of the Race—Its Own Conservation, published in 1917. He recounted how much the state spent treating disabled people each year, and noted that nothing was spent on preventing their reproduction. Ohio had no laws requiring the mandatory sterilization of the disabled as many states did, but a 1904 law did prohibit “the granting of marriage licenses to insane, epileptic and mentally defective persons.”

Nazi Germany put the theories of eugenics into practice. In 1933 they passed the Law for the Prevention of Offspring with Hereditary Diseases only a few months after Adolph Hitler assumed power, which allowed for sterilizing the disabled. But this did not go far enough toward Hitler’s goal of a healthy, pure German nation, so in 1939 the Nazis turned to euthanasia. They established six official killing centers scattered throughout the country that exterminated disabled adults. One of the most notorious was the Hadamar Psychiatric Institute, where more than 10,000 mentally ill were killed. In 1941, Hitler officially put a stop to the killings because of public opposition, but the program continued in secret. Beginning in 1943, Hadamar began to function primarily as a center for killing children. The “children’s campaign,” in which physically and mentally disabled youth were killed, continued even after the war ended.

In 1946, Allied forces held war crime trials in Nuremberg for some of the doctors accused of the eugenics killing. In 1947, three were sentenced to death.